Thanks for reading “Made With Care,” a deep dive into the cultural roots of the care crisis and how parenting and caregiving is a wild, meaty and profound ride that men ignored forever. I really care about care and so glad you do too.

For more on the subject, check out my new book “When You Care: The Unexpected Magic of Caring for Others.” It’s my 300ish page attempt to make the invisible work of care visible, by uncovering why we don’t really value care in our personal and collective lives, and what the world would like if we did.

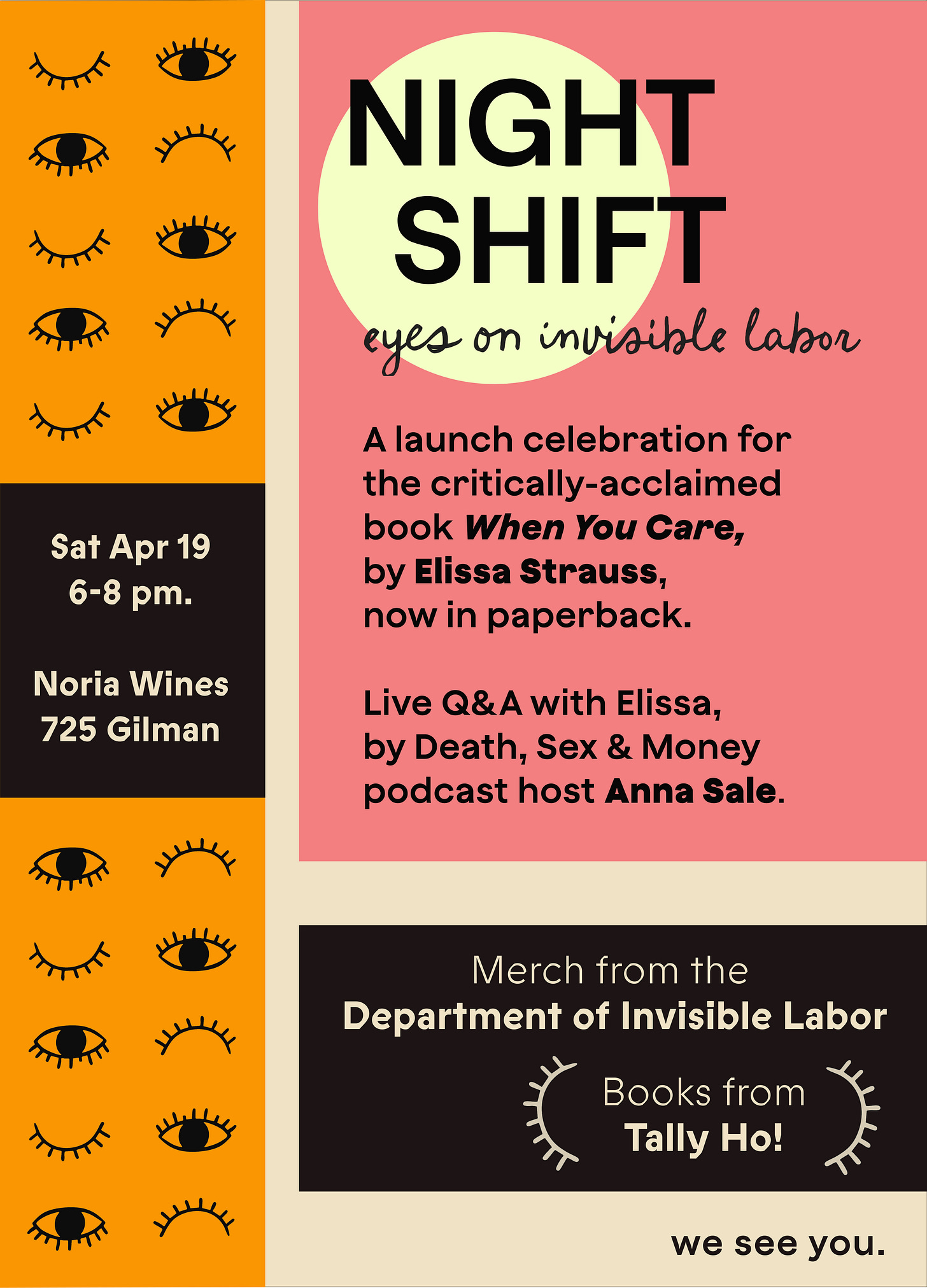

NEWS: PAPERBACK COMES OUT ON APRIL 9! You can pre-order it here. I’m having an event in Berkeley on April 9 with and the Department of Invisible Labor. More on that below.

This week’s virtual mini-earthquake came to us from singer Chappell Roan, who shared a pretty dismal report on the state of her parent friends on the podcast Call Her Daddy.

"All of my friends who have kids are in hell. I don't know anyone who's happy and has children at this age... anyone who has light in their eyes," she said.

The virtual “yay motherhood” and “nay motherhood” teams quickly assembled themselves, many dividing up along predictable lines — as I observed things, conservatives seemed to be over-represented on the “yay” side, and progressive/ self-identifying feminists on the “nay” side — and made a lot of noise. People were mad she said it. People were glad that she said it. People were mad at those who were glad that she said it. People were mad at those who were mad that she said it.

My response: Here we go again. I hope we do it better this time. (Some did. Most didn’t.)

This post is about how I wish the conversation about parental happiness could go.

I’m gonna start by (not exactly) answering the question of whether or not parenting makes you happier. It’s a question I find not at all useful when asked on an individual basis, and you will see that frustration reflected in the answer. I think it is a far more useful question when asked on a collective basis, even if the answers it yields still paint a rather incomplete picture.

And then I’m gonna answer a question I like much better, and think it is the one we should be asking when contemplating motherhood on individual terms. What is that question? Read on.

Does parenting make parents happy or unhappy?

Upshot: It makes some people happier and others unhappier; it makes many people neither happier or unhappier, but still feels to them as deeply worthwhile; and the biggest factor on determining happiness on a collective basis is how much social support parents get.

When we think about happiness on an individual basis, there are so many variables at play, variables that make any kind of universal answer impossible. These include:

What kind of baby, and later, kids do you have?

Are they good sleepers?

What kind of partner do you have? Are they helpful?

What kind of baggage do you have around being a “good” mom or parent? Some go in feeling like they have to be constantly available, always even-tempered, and are filled with guilt and shame when they aren’t. Others go in expecting far less of themselves and feel better as a result. (I was in the latter camp — and these lower expectations really served me, I think.)

Did you have a relatively easy birth or a traumatic birth?

Did you have postpartum depression or anxiety? Or ongoing depression and anxiety?

In the grand lottery of human-making, did your kids come out as people you easily connect with?

(There are many other wild card variables, but I think you get the drift by now. Parenting is a relationship between two or more unique humans at a unique moment of time.)

We all have very different answers to these questions. And, the answers to these questions can change over the course of a lifetime — or even the course of a day.

My writing has made it clear that I have found parenting to be a net good in my life.

That said, I’m not a big baby person, and didn’t feel so strongly about the “magic” of parenting during the infant and toddler years. It took getting to that point where my kids could speak, and weren’t constantly at risk of unintentionally, or intentionally, harming themselves or others, for me to find parenting as deeply rewarding as I do.

Right now, with kids ages 7 and 12, I am really frigging happy being their mom. Their still squishy cheeks, their good and bad jokes, their rich, child-mind wisdom, the sight of them cuddling with each other, their smiles when I pick them up at the end of the day — it is all a source of incandescent delight for me. Some of the greatest delight I have ever known. But who knows what I will be feeling in five years from now.

When we move away from a focus on individual happiness, and subjective factors, to a focus on parents’ collective happiness and more objective, and mutable, factors, there are other questions to ask:

Do you have help? A supportive community?

Can you afford paid help for things like babysitting, housecleaning, or food preparation?

Do you have paid leave? Does your partner have paid leave?

Do you have access to reliable and affordable childcare, including preschool, summer camps, and after-school? Or, can you afford to care for your child yourself?

The answer to these questions from way too many parents is no, no, no, no, and no. If I could rewrite Roan’s soundbite, I would add in something about how none of the parents she knows are well-supported. How they are lonely, burnt out, touched out, and overwhelmed because they live in a culture that doesn’t support them, value them, or, my biggest pet peeve, have curiosity about them and treat them as interesting people doing interesting things. Should she have included something like this, it would have taken us away from the debate about whether or not parents are happy, and brought us into a conversation about the root causes of way too many parents’ misery. (Evergreen reminder: all the social support in the world won’t erase all the stress and pain of parenting for everyone. It is hard work! For some way more than others! But it will go a very long way.)

Every time we talk about how hard parenting is, we should be making it clear that it doesn’t, at least in part, have to be this way. Hell, as Roan describes it, is not the natural habit of parents. Because if parental misery sounds inevitable, it gives us little reason to fight for change. But if the misery sounds like it is a result of an overly individualistic culture and a government that does shamefully little to support family life, then statements about parental unhappiness can become a rallying call to fight for change.

Also, when we put parental unhappiness in a social context, we allow for the both-ness of it all. We make room for the millions of moms and dads who feel joy from their kids and appreciate the philosophical and spiritual challenges parenting brings them, but also end each day depleted and bitter because they are parenting without support during a time when our expectations for parents are higher than ever and our community ties, social contract and governing institutions feel scarily fragile.

Nearly every parent I know lives inside that both-ness. We love our kids, find meaning in parenting, and also find parenting way more stressful than it needs to be. And yet the both-ness rarely shows up in the social media cage fights on the subject of parental happiness.

In my book I dig into what we know about why parents are unhappy, and the data overwhelmingly points to the lack of support piece.

Parents aren’t that different. There are plenty of studies showing that becoming a parent makes one happier, while others show the exact opposite. But what interests me more is what the research tells us about why parenting makes us unhappy. Is it that the person-to-person act of caring for a child is overall misery-inducing? Or is it the stress that comes along with parenting, like feeling there is never enough money or time, that ruins the experience?

Two large studies, and a handful of smaller ones, found that it’s most often the latter. In 2019, economists David Blanchflower and Andrew Clark published a study for which they examined life-satisfaction data collected from over 1 million people over the course of ten years in thirty-five European countries. They discovered a broad happiness dip among parents but then quickly determined that this was the result of the parents not feeling like they had enough money. “The negative effect of children comes from their effect on financial difficulties,” they write in the paper. When economic struggles were taken out of the equation, children raised the happiness of parents in the vast majority of cases. Parental income and education also played a role, as well as the country’s overall income and the level of social support.

Sociologist Jennifer Glass came to a complementary conclusion after reviewing data on parenthood and happiness from nineteen European countries plus New Zealand, Australia, and the United States. In Russia, France, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Spain, Hungary, and Portugal she found that parents range from being “slightly happier than nonparents (increases in happiness of about 1 percent compared to nonparents for Russia and France) to significantly happier than nonparents (increases of up to 8 percent from the baseline level of nonparents).”

There is a clear and obvious link between the availability of family friendly government policies in a country and the level of happiness of the parents, with paid-leave and childcare subsidies mattering the most. Considering the United States offers very little in the way of support to parents and is the only industrialized nation in the world without a universal paid-leave policy, it’s unsurprising that American parents ranked as the least happy, by a long shot.

“If you ask parents, ‘Is it parenting that’s making you unhappy?’ they’re not going to tell you it is. They’re going to say they love their

children. They adore their children. It’s the best thing they’ve ever done. I say all those sappy things, and my kids would never in a million years think that it was a bad idea to have children,” Glass told me. “But when you ask them to rate their happiness overall, that’s where you see the happiness dip. It’s not that they’re unhappy that they are parents. They’re unhappy that they’re being forced to parent in a society that provides virtually no support.”

The question I would rather parents ask themselves

While I do think there is real utility to talking about parental happiness on a collective level, I don’t think it is the best line of inquiry for individual parents when contemplating what parenthood means to them. Here I’m talking about the inner, soul-searching part of parenthood, the deep tissue struggle to make sense of it all.

Instead of parents asking whether or not parenting makes them happy, I think they should ask what kind of meaning they are getting from the experience, and how the whole range of feelings and experiences connected to raising kids, the good, bad, and ugly, contributes to that meaning-making. Here’s what I wrote about this in my book:

Perhaps the psychological benefits of care would be easier to see if we moved away from happiness and focused on meaning. There is plenty of convincing research making this point about caregivers to old, ill, and disabled individuals, as well as parents who report finding parenting more meaningful than their work or leisure time. One study found that the more time people spent taking care of their children, the more meaningful they found their lives. But they weren’t necessarily happier.

“Satisfying one’s needs and wants increased happiness but was largely irrelevant to meaningfulness. Happiness was largely present oriented, whereas meaningfulness involves integrating past, present, and future . . . ,” the authors write. “Happiness was linked to being a taker rather than a giver, whereas meaningfulness went with being a giver rather than a taker. Higher levels of worry, stress, and anxiety were linked to higher meaningfulness but lower happiness. Concerns with personal identity and expressing the self contributed to meaning but not happiness.”

Happiness demands ease, which is not a characteristic of care, while meaning demands friction and growth. We get meaning from the things that matter to us, that push us to see ourselves more clearly, and, on good days, grow. Meaning, like, not coincidentally, care, takes time. Care is not a happy or healthy quick scheme, even in the best of circumstances. We must return, again and again, to the person and situation that wants something from us and explore our place, our meaning, in the arc of that singular, ever-shifting relationship.

May we keep working towards less binary (the subject of my next newsletter), more expansive, more grounded in detail, fuller, deeper, richer conversations about parenthood and care overall. I really believe that building a world that adequately supports parents and caregivers depends on it.

Paperback launch!

Message me for more details — or just show up. Please come say if you do!

Loved this piece and the call to ask better questions of parents- so many conversations could benefit from this mindset! I also think that as time goes on and we adjust to the added work and responsibilities, it becomes easier to find the joy in parenting. Early motherhood was tough for me and it’s taken me years to transition into the role, but now almost 3 years (and multiple kids) in, I feel much lighter and more fulfilled.

Happiness is such a poor measure for a mutlitude of life experiences, especially complex ones like parenthood. Excellent piece, Elissa.